Originally posted in FA magazine.

When financial advisors have conversations about investments with their clients, there’s usually something missing—a dialogue in which the advisor can discover a client’s particular perspectives on important money issues.

I’m talking about those issues that will inevitably lead to the flourishing or floundering of any well-intentioned plan. It’s awfully difficult to be on the same page with our clients if there is no process for identifying which page they’re on.

The process I’ve developed is called the “Fiscalosophy Dialogue,” where the conversation merges fiscal discussions with the client’s particular philosophy on foundational financial topics.

Before I go into the particulars, I want to introduce a framework for talking with clients. It has three steps:

- First, gain permission. It is unfair to blindside clients or prospects with a question they didn’t expect, may not be prepared for or that feels out of context. The first thing to do before introducing a novel dialogue is to let them know what you’re seeking to inquire into and why you feel it is important to the process and relationship. Gaining permission from the clients first raises their awareness level and the degree of engagement in the dialogue itself.

- Then engage in the dialogue. You can now begin to engage in the conversation.

- Finally, anchor what you have learned about the client to the process ahead. Begin by saying something to the client like, “Now that I’ve heard your perspectives/story/thoughts on this matter, I would suggest we look at doing the following _____.” This tells the clients that you “hear” them, and that you are taking their views and experiences and making them foundational to the work you will do and the strategies you will suggest with them.

Important Money Matters

The design of the Fiscalosophy Dialogue is a left-brain/right-brain inquiry (what do you think and how do you feel?) to understand a client’s behaviors and habits in eight categories critical to the planning process: 1) their debt, 2) their saving, 3) their spending, 4) their insurance, 5) their investment in the stock market, 6) their needs for their children, 7) their desire to give to others and 8) their feelings about retirement.

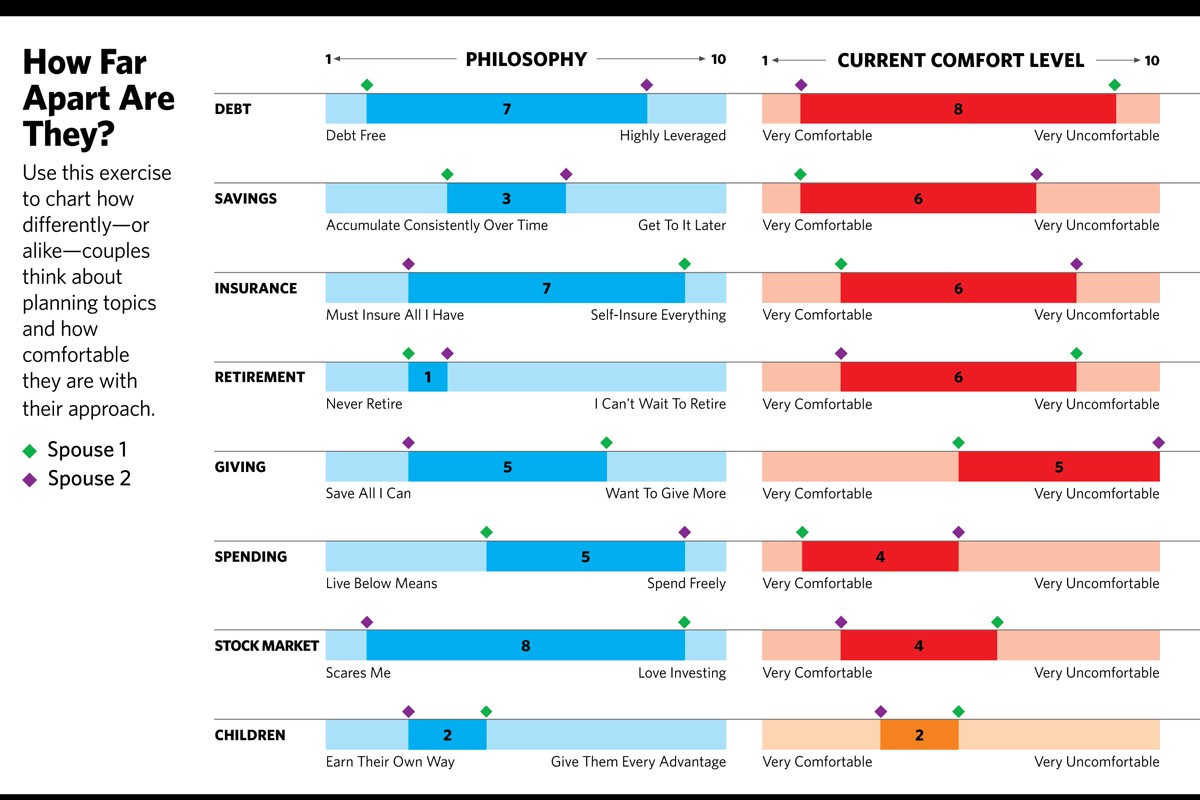

In my “Return on Life” process, I’ve created number scales for things like “savings” and “retirement” and “children” and asked couples to pick a number on the scale that corresponds to their attitudes about that topic and how comfortable they are currently feeling about it. For example, their philosophy about debt may lie on a graph point somewhere between the preference of being completely debt free and being OK with a lot of debt to fund the things they would like to do. After that, there’s a “comfort” bar that shows how comfortable they are with their current position on the map.

Here are some topics. Clients choose a point on the scale between them to demonstrate their attitudes:

- Debt: Would you rather be debt free … or are you OK being highly leveraged?

- Saving: Would you like to accumulate consistently over time … or would you like to get to it later?

- Spending: Would you like to live below your means … or would you like to spend freely?

- Insurance: Do you feel you must insure all you have … or would you rather self-insure everything?

- The stock market: Does it scare you … or do you love investing?

- Your children: Would you like them to earn their own way … or would you like to give them every advantage?

- Giving: Would you prefer to save all you can … or do you want to give more?

- Retirement: Do you never want to retire … or can you not wait to retire?

What The Clients Learn

One thing we know about people is that they love to learn more about themselves. In this exercise, they learn about their perspectives, the experiences that shaped those perspectives, the areas where they have synchronicity or lack thereof, and the possible disconnects between their stated philosophies and their behaviors and habits. The bonus for you as the advisor—in addition to learning all these things about your clients—is that you learn where they need immediate attention because it will show up as a “code red” discomfort level in their readout.

When couples plot these points together, the bar charts show where they are on the same page and where there are discrepancies:

The chart shows couples where they agree and where they need further discussion. Although most couples tacitly understand their different feelings about money, these feelings are usually unspoken and ignored. This report gives them the ignition to talk through where they might meet in the middle philosophically, and how their current views will impact their future possibilities.

This dialogue also gives us points of reference for how those perspectives were formed. We either had an experience that informed our view, or we witnessed someone else’s experience and took away an opinion on the matter. It might be an event we witnessed, read about or otherwise observed. There are stories behind every viewpoint.

People have reasons for behaving the way they do—the chapters in their life that made an impact on them. Some clients, for example, may have had a loved one who never took time off, never spent a dime on enjoyment, and died early. That informs the way the clients feel about spending freely. So later in the conversation, they may need to come to grips with how their free-spending ethos is impacting their savings habit or desire to retire.

Other clients may talk about giving their children every advantage because their parents couldn’t afford to give them anything. Others may say the opposite—instead, they saw someone with every advantage lack incentive and motivation, and the person frittered those advantages away.

As an advisor, are you in better stead in the relationship knowing both these perspectives and the stories that have shaped them?

If any clients use the debt slider to suggest they believe in being totally debt-free, my first question is going to be, “Tell me how you arrived at this perspective.” I want to know the story behind the view. Granted, clients may arrive at an unhealthy or unproductive viewpoint because of an experience. Maybe they avoid markets because their 401(k) was fractured. As an advisor, you will be better off knowing where they stand and how they arrived there. At the very least, you can sympathize with their experience before trying to adjust their perspective.

Ultimately, the best result of a Fiscalosophy discussion is to know and understand the experiences that have made deep impressions on clients and their money. We need to understand both the experiences they’ve had and the conclusions they have drawn. We’re primarily in the people business. We just happen to work with their money.

Another frequent outcome of this dialogue is that clients see the disconnect at times between what they say they believe (their philosophy) and the level of discomfort with their current situation. This disconnect is the crux of behavioral finance—in which we fool ourselves into unhealthy financial habits and behaviors. Like it or not, it’s part and parcel of the modern advisory relationship to help clients deal with their financial reality and to acknowledge the role they play in their own success or lack thereof. At the end of the day, what’s in the best interest of your clients is to act in their own best interest.

Mitch Anthony is the creator of Life-Centered Planning, the author of 12 books for advisors, and the co-founder of ROLadvisor.com and LifeCenteredPlanners.com.