Originally posted at fa-mag.com by Mitch Anthony, May 1, 2021.

Last year I was approached by two professionals with an interesting idea for a social experiment with retirees.

One of the men was a serial entrepreneur named Bob Ahmann. The other was a retired engineer named Darryl Solie (I say “retired,” but he’s always involved in some big project). Both had retired from careers at IBM and knew many other ex-IBMers who, frankly, were bored in retirement. Engineers are “meddlers” and problem-solvers by nature, and when they no longer have any problems to solve, ennui can begin to set in.

Bob and Darryl knew that I’d be interested in their idea because my book The New Retirementality had been warning people for the last two decades about just those kinds of retirement woes. So here’s the original idea that Bob dreamed up:

He and Darryl had located a local medical technology business that needed proprietary software to be developed. “What if,” they pondered, “we could get some retired engineers to develop the software?”

The novel idea was that instead of taking pay for their labors, they would give the proceeds to a local charity (in this case, the local Ronald McDonald House).

There were three clear winners in this idea:

1. A local business not only acquired a much-needed technology upgrade, but also reaped the benefit of being able to help its community.

2. The retirees got a fresh challenge on their hands—one that they could work on as little or as much as they wanted to each week.

3. The charity got a new income source—without having to solicit the funds.

After I joyfully accepted their offer to join the cause, we knew our first task was to find an identity. After much wrangling with words, we settled on the name “ExperiCorps.” Our aim was to help the world capitalize on the untapped experience sitting latent in the retirement playgrounds.

When we approached people at the medical technology company, they liked the idea of making a donation in kind (equal to what the project would have cost them otherwise). When we approached the crew of retired engineers, they loved the idea of breaking off some cobwebs and taking on a new challenge. They ranged in age from their late 50s to early 70s and had plenty of vigor and perspicacity to spare.

The engineers met with the company to get a clear understanding of what kind of software was needed and then got right to work on the project. Within two months they had a prototype in place.

Eventually, the business wrote out a check for $11,000 to the Ronald McDonald House, and we all had a merry time presenting this gift to the charity. Later on, checks for $34,000 were presented to Ronald McDonald House and other local charities as the software got some updates.

The initial project was a success, but then we faced a dilemma in deciding how to bring the project to other parts of the country—and that was figuring out where business opportunities would magically appear. The idea falls apart without local businesses knowing that such opportunities exist. The first project came from friendships and brainstorming. Where would other projects come from?

That’s when Bob had a second epiphany and added a new element: We could use the concept to help inventors bring their ideas to market. Millions of inventions never see the light of day, even though a good percentage of them have commercial potential. Inventors are not necessarily experts at marketing and sales, so their brainchildren end up gathering dust and rust. Bob was a successful inventor himself and had been looking for a company to sponsor his own intellectual property. He wondered how many other people had this problem.

He also had extensive experience in commercializing other people’s creations. He had spent years developing processes, networks and resources and had tapped some world class experience in helping others commercialize their ideas.

He decided to call his patent lawyer and ask if any of his clients could use the same kind of help. The attorney thought it was a wonderful idea. He has many clients who get patents and have absolutely no idea how to move them forward.

Intellectual property typically requires not only a sponsoring company but also a little technical help in cleaning up some of the rough edges—which is likely the primary reason inventors have trouble. So having access to an executive and a professional network of engineers, programmers, etc.—people who could help with the process—would be priceless to the inventor.

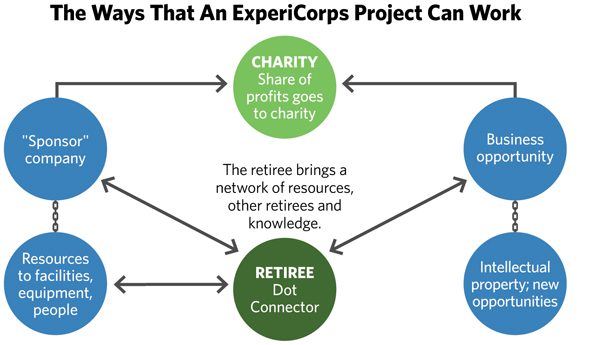

That’s how the business model for ExperiCorps evolved and became much easier to embrace and understand. The intent is still to pursue business opportunities, but the mechanism we now use is the commercialization of intellectual property. That allows us to take advantage of all sorts of different skills and talents. What do engineers, programmers, technical execs, etc. like to do better than jump on a new idea?

We subsequently talked to other lawyers whose inventor clients had the same problem. Just think of all the business opportunities that might be generated with a little help. We figured that if ExperiCorps could put together a small team to assist frustrated inventors, why wouldn’t those inventors share a percentage of the licensing proceeds—particularly if it’s for charity?

So now we have four winners: the charities; the business sponsor; the inventor; and the retirees, who have something to work on that can provide extreme personal reward. That is the ideal scenario!

Our project also helps charities transform their funding practices. Many of the inventions will produce licensing income, which can offer the charities a constant income stream (meaning they’ll have to do less soliciting).

Since there are no critical deadlines, this type of work should suit retirees. The effort generally involves organizing discussions and meetings with key people. It doesn’t have to take much time out of any one day and is easy to schedule. Retirees can bring their experience back to productivity with very modest time commitments … and see their efforts help those in need.

Those looking for some extra income can also benefit from the ExperiCorps model, since they could take half of the proceeds in kind as pay. A minimum of 50% to the charity from the contributing retiree is required, however. In our initial projects, the contributing retirees donated 100% to the charity, but we also recognize there will be those who could do with the extra income—and the professional assistance available from ExperiCorps can help generate that.

Bear in mind that this idea is not limited to software, and one could capitalize on any type of intellectual capital and experience. It’s simply the commercialization of the property that needs to be figured out and then a connection needs to be made with a firm that could use it. Things accelerate from there.

There are enough retirees out there who would jump at the chance to make a difference in the world around them while putting their brain potential to use.

We want to know what you think. Got ideas? Drop us a line at [email protected].

Mitch Anthony is the creator of Life-Centered Planning, the author of 17 books for advisors, and the co-founder of ROLadvisor.com and LifeCentered Planners.com.