Originally posted in Financial Advisor (fa-mag.com) on Sepember 1, 2019

As we approached the tee for the eighth hole, a buddy of mine said to me, “Last year I stood on this tee box with Advisor Joe Schmo, and you were up in the fairway ahead of us. He turned to me and asked, ‘You’re friends with Mitch, aren’t you?’” My friend nodded that he was. The advisor (who was my friend’s advisor) said, “Well, one day I’m going to get his money.”

Needless to say, my friend was appalled at the comment and seriously wondered how he had ever become entangled with this fellow. I told my friend, “This guy doesn’t have clients; he has clients’ assets. He is fossilizing as we speak, and one day someone truly interested in the clients’ well-being will be serving his former clients.”

I’ve had the honor of closing many a convention with a speech stressing the importance of building relationships with people—not just their portfolios. Immediately after the last speech, attendees are often treated to a happy hour reception. I can’t count the number of times I’ve overheard advisors sharing client stories with one another and prefacing their story with, “I’ve got this $8 million client, and …” Whenever I hear that introduction, I wonder to myself, “What if that person heard himself being characterized in that manner?”

Perhaps you find me a bit prickly about this, but I suspect we would all do well to periodically examine how we frame others. Our assumptions about what matters and who matters naturally flow into that framing. In the world of “who” everyone is important, but in the world of “what” the numbers diminish quickly and radically.

Advisor Joe Schmo saw the money as the client, not the client as a client. He was in the “what” side of the business instead of the “who” side of the business. In Dr. Seuss’s book Horton Hears a Who!, Horton the Elephant hears a cry for help coming from a speck of dust. He can’t really see anything, but he decides to pay attention to the plea. It turns out that the speck of dust is home to the “Whos,” and they live in their city of Whoville. Horton agrees to help the Whos and their home, but he gets much grief from his neighbors who refuse to believe that anything could possibly live on such a little speck. Ultimately, Horton stands by his credo, “A person’s a person, no matter how small.”

Embedded in financial services sector thinking is the insidious idea that assets represent the person. Certainly assets represent people’s efforts, the direction they chose, their good (or poor) fortune, as well as their financial habits. But assets don’t tell us who those people are any more than their car can tell us how far they’ve come or their shoes indicate how well they’ve walked in life. It’s a twisted ethos that tacitly agrees with the idea that crossing a particular line on net worth makes a person more valuable to society at large.

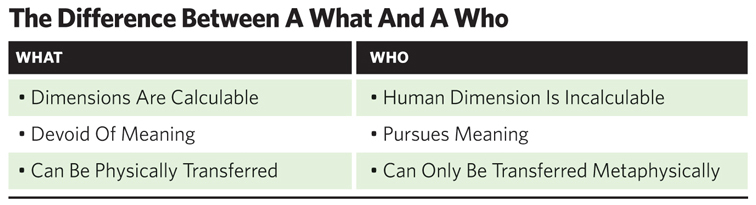

One can measure what a man or woman possesses but cannot measure what possessed them to get to where they are. Motives are not measured but weighed … and even then, the weight is felt but not calculable. Humans resent being sorted, ranked or typecast in any way, shape or form. The human spirit bristles against categorization. Humans want to be heard before they are told and want to be understood before they are underwritten. In their hierarchy of needs, the appreciation of them as people precedes the appreciation of their assets. There is one set of rules for handling the “what” and a completely separate and transcendent set of principles for relating to the “who.” When people keep these things straight, good things happen to them.

Why is this discussion important? Because in this profession you cannot survive—or more certainly, you cannot thrive—without serving people with significant substantive holdings. But it’s good to remind yourself often that being a person with substance doesn’t guarantee being a person of substance—and vice versa. People are people, and stuff is stuff. We are here to serve the “who” and manage the “what.”

It’s certainly true that we cannot take on as clients every person we like who lacks assets, as we would inevitably go out of business. But with asset minimums and net worth thresholds, we could just as easily miss wonderful opportunities for serving some remarkable “whos.” There’s got to be some moral latitude and balance in how we determine who we can and will not serve.

A financial planner in Pennsylvania told me the story of a man who came to him deeply in debt and with negligible assets; in fact, he was upside down in net worth. He told the planner he needed help to plan his way out of his situation. The planner told me that he had always left room in his month for pro bono or lower-priced planning work—especially where he sensed the client’s aspirations. He agreed to develop a plan for this fellow, and the man stuck to the plan. The man was a software engineer working with a tech start-up. Five years later, the man’s company was sold and he was rewarded with a $75 million dollar payday. I’m sure you can guess whom he entrusted assets with. The advisor told me, “I had no idea anything like that would happen, I just wanted to see him turn his situation around.”

Keep the “who” straight, and the “what” will come. Conversely, if you give the “what” precedence, be careful of “who” you might become. In an industry that places great meaning on the “what,” and pressures you to do so as well, it might be best to follow the maxim of Horton the Elephant: “A person’s a person, no matter how small.”

Mitch Anthony is the creator of Life-Centered Planning, the author of 12 books for advisors, and the co-founder of ROLadvisor.com and LifeCenteredPlanners.com.